Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research demonstrates that subtle changes in electrical resistance under a magnetic field can be used to chart the complex electronic structure of high-temperature superconductors.

Sondheimer magneto-oscillations offer a temperature-independent probe of Fermi surface reconstruction in underdoped cuprates, providing insights into the pseudogap phase.

Determining the Fermi surface topology in underdoped cuprates remains a central challenge due to the limitations of conventional quantum oscillation techniques at high temperatures. This work, ‘Sondheimer magneto-oscillations as a probe of Fermi surface reconstruction in underdoped cuprates’, proposes Sondheimer oscillations-a semiclassical magnetoresistance effect-as a robust alternative for mapping the Fermi surface and probing its reconstruction. By analyzing the frequency-dependent response of these oscillations, we demonstrate the potential to differentiate between various scenarios, including large Fermi surfaces, spin density wave reconstructions, and fractionalized Fermi liquid states, without relying on low-temperature quantization. Could this approach offer a new pathway to understanding the pseudogap phase and the complex interplay between electronic structure and superconductivity in these materials?

Unveiling the Subtle Symmetry of Cuprate Superconductors

The enigmatic behavior of underdoped cuprate superconductors in their normal state continues to challenge established theories of metallic conductivity. Unlike conventional metals where electrons move freely, these materials exhibit properties that suggest a fundamentally different organization at the microscopic level. Decades of investigation have revealed that the normal state isn’t simply a disordered version of the superconducting state, but rather a complex entity with its own unique characteristics – including a resistivity that increases linearly with temperature, a stark contrast to the expected quadratic behavior. This defiance of conventional metallic behavior points to the presence of competing electronic phases and a breakdown of the widely-used Fermi liquid theory, implying that the very foundation of how electrons interact within these materials requires re-evaluation and a novel theoretical framework.

Intriguing experimental results, notably the Yamaji effect – a sharp change in the angle dependence of the resistivity – strongly suggest that the electronic structure of underdoped cuprates isn’t what it seems. This effect, alongside others, points to a subtle breaking of the symmetry normally expected in these materials, implying that the arrangement of electrons isn’t uniform or predictable. Consequently, the Fermi surface – a map of electron energies and momenta – isn’t the simple, continuous shape predicted by standard metallic theory, but rather undergoes a reconstruction, forming “hot spots” and altered shapes. This reconstruction isn’t merely a static distortion; it appears to be dynamic and linked to the peculiar charge ordering observed in these materials, hinting at a complex interplay between broken symmetry, altered electronic topology, and the emergence of superconductivity.

Conventional techniques for mapping the electronic structure of materials, such as Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy (ARPES) and theoretical models based on simple band theory, consistently fail to fully account for the peculiar behavior observed in underdoped cuprates. These methods often assume translational symmetry and a well-defined quasiparticle picture, assumptions that break down in these complex materials. The resulting electronic structures predicted by these approaches diverge significantly from experimental findings, particularly regarding the presence of “shadow” Fermi surfaces and the intricate patterns revealed by the Yamaji effect. This disconnect suggests that more sophisticated theoretical frameworks-capable of incorporating strong electron correlations, charge density waves, or other forms of broken symmetry-are essential to accurately describe the normal state of these enigmatic superconductors and ultimately unlock the secrets to their high-temperature superconductivity.

Mapping the Electronic Landscape: Experimental Probes

Angle-Resolved Photoemission Spectroscopy (ARPES) and Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) are surface-sensitive techniques used to directly map the electronic band structure and, critically, the Fermi surface of materials. ARPES measures the kinetic energy and momentum of electrons emitted from a sample upon irradiation with photons, allowing reconstruction of the E(k) dispersion relation and visualization of the Fermi surface topology. STM, conversely, probes the local density of states by scanning a conductive tip over the sample surface, providing real-space images of the Fermi surface and revealing any reconstructions or distortions arising from factors like symmetry breaking or charge density waves. Both techniques are capable of resolving features on the scale of 10^{-3} eV in energy and 10^{-3} Å in momentum space, allowing detailed characterization of the electronic structure and identification of topological features.

Fermi arcs are atypical linear dispersions in the electronic band structure observed in momentum space, representing electronic states that connect projected Dirac points on the Fermi surface. Their emergence signifies a breakdown of the conventional Fermi liquid model, which assumes well-defined quasiparticles and a sharp Fermi surface; instead, these arcs indicate the presence of gapless excitations and broken symmetry within the material. Specifically, the presence of Fermi arcs is commonly associated with topological phases of matter and Weyl or Dirac semimetals, where band crossings are protected and give rise to these unconventional electronic states extending from the Dirac points and terminating within the bulk band structure, rather than connecting different points on the Fermi surface as in traditional metals.

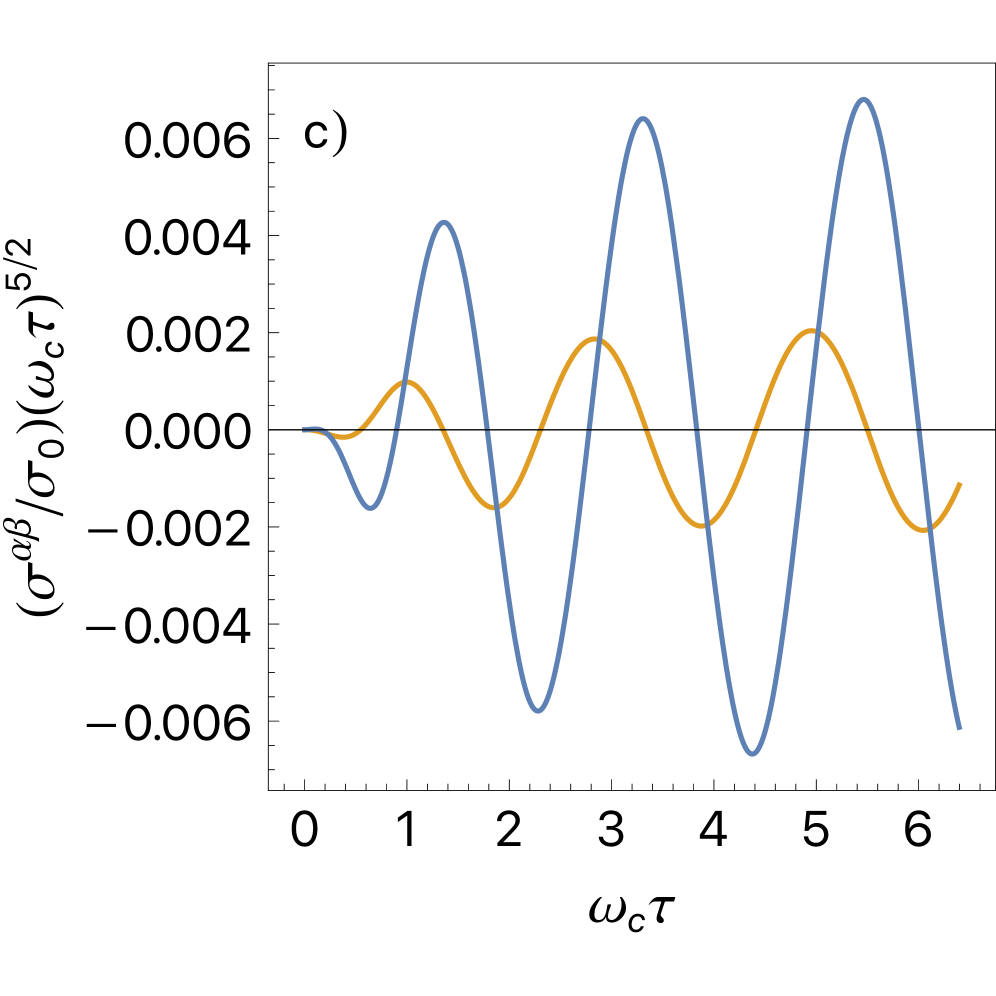

Quantum oscillations, specifically the Shubnikov-de Haas effect, manifest as periodic variations in electrical resistance as a function of magnetic field. Analysis of the oscillation frequency, known as the cyclotron frequency \omega_c, allows for direct determination of the carrier density n via the relation \omega_c = eB/m^<i>, where e is the elementary charge, B is the magnetic field, and m^</i> represents the effective mass of the charge carriers. Precise measurement of the effective mass, in conjunction with the carrier density, provides crucial information regarding the band structure and the nature of the charge carriers within the material, differentiating between Dirac-like or conventional Fermi liquid behavior even in the absence of long-range order.

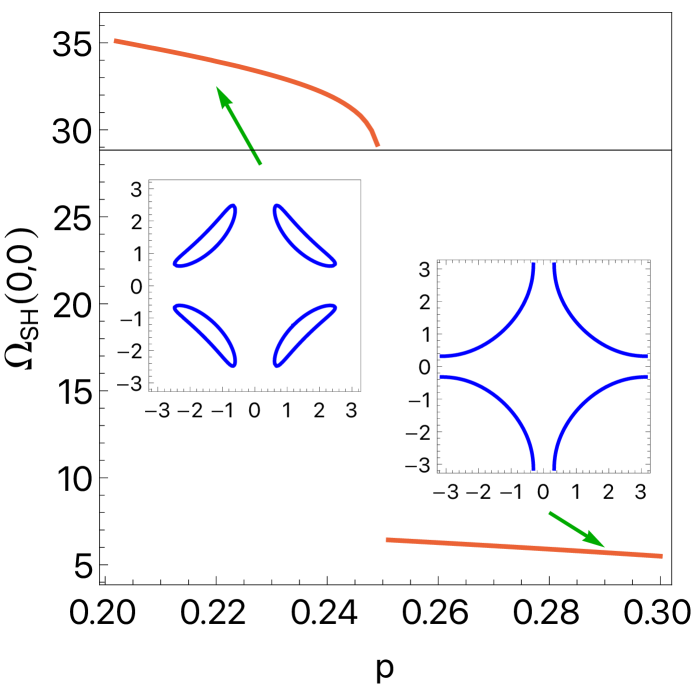

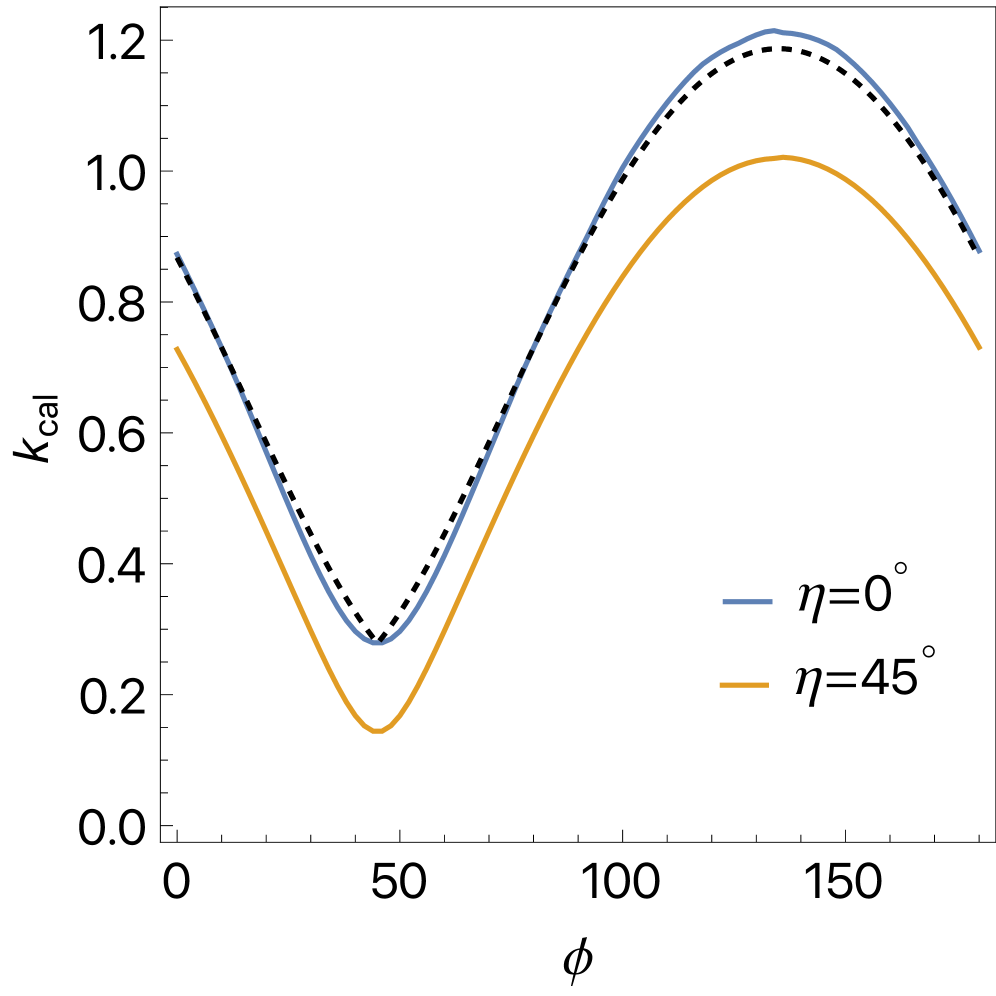

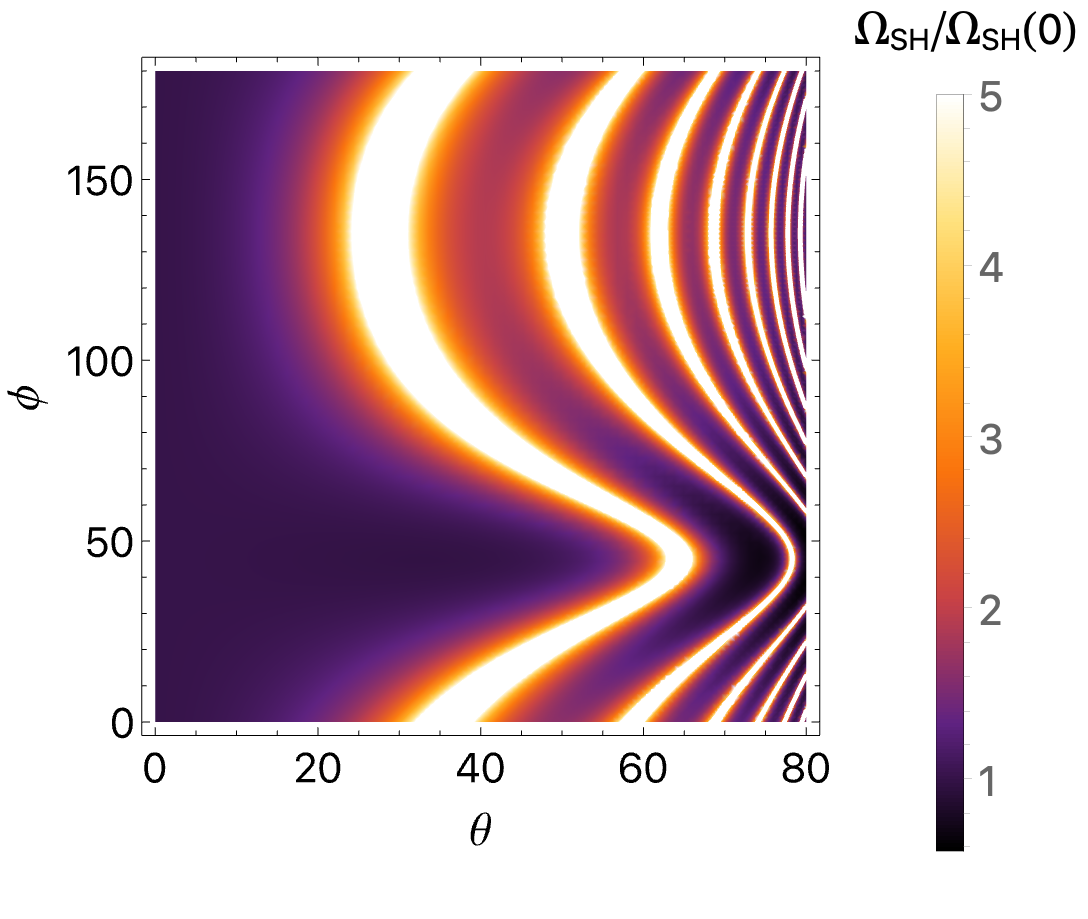

Magnetoresistance analysis, specifically the observation of Sondheimer oscillations, provides an alternative means of characterizing the reconstructed Fermi surface. Sondheimer oscillations arise from the interference of electron waves scattered by imperfections in a material, and their frequency is determined by a relationship incorporating several key parameters: \omega_{SH} = \frac{\hbar k_F^2}{e l} , where \hbar is the reduced Planck constant, k_F is the Fermi wavevector, e is the elementary charge, and l represents the mean free path. Crucially, the Sondheimer frequency is directly proportional to the square of the Fermi wavevector, allowing inference of the Fermi surface curvature. Furthermore, the oscillation period is affected by the film thickness – thinner films exhibit broader oscillations – and is dependent on the magnetic field orientation relative to the sample. Analyzing these oscillations enables determination of the Gaussian curvature of the reconstructed Fermi surface without requiring direct imaging techniques like ARPES or STM.

Theoretical Frameworks for Deciphering the Electronic State

Tight-binding models represent a computational approach to determining the electronic structure of materials by focusing on the interactions between atoms and their immediately neighboring atoms. These models approximate the solutions to the Schrödinger equation by linearly combining atomic orbitals, enabling the calculation of energy bands and wavefunctions. Crucially, tight-binding calculations are well-suited for simulating the effects of Fermi surface reconstruction, a phenomenon where the shape of the Fermi surface changes due to periodic modulations of the crystal lattice, such as those induced by charge density waves or spin density waves. By accurately representing the relevant atomic orbitals and their interactions, these models can predict the resulting changes in the electronic band structure and the altered Fermi surface topology, providing insights into the material’s electronic properties and behavior.

The Ancilla Layer Model proposes a theoretical framework for understanding the fractionalized Fermi liquid state observed in certain materials. This model introduces an additional layer – the “ancilla” layer – which does not directly participate in the low-energy physics but influences the behavior of the primary layer through interlayer interactions. Specifically, it posits that the strong Coulomb interactions within the primary layer lead to the decomposition of electrons into independent spin and charge carriers – a hallmark of fractionalization. The ancilla layer serves to screen these interactions and stabilize the resulting fractionalized excitations, providing a mechanism to explain experimental observations like unusual quasiparticle behavior and deviations from Fermi liquid theory. The model predicts specific spectral functions and transport properties that can be tested through spectroscopic measurements and transport experiments, offering a pathway to validate the existence of this exotic state of matter.

Charge order, manifesting as a periodic modulation of the electronic charge density, is now widely considered a primary mechanism influencing Fermi surface reconstruction in correlated electron systems. This modulation creates a periodic potential that alters the momentum distribution of electrons, leading to distortions of the Fermi surface from its expected free-electron form. Experimental evidence, including resonant X-ray scattering and scanning tunneling microscopy, consistently demonstrates the presence of charge order in materials exhibiting Fermi surface reconstructions. The wavelength of the charge density wave, and therefore the resulting Fermi surface distortion, is often commensurate or in a simple rational relationship to the underlying lattice, though incommensurate charge order is also observed.

Current theoretical understanding of the normal state in cuprate superconductors indicates it is not a simple, featureless system, but rather a complex state arising from the interplay of multiple electronic and structural phenomena. Specifically, charge order – the periodic modulation of charge density – coexists with broken symmetry states, and both contribute to the emergence of fractionalized excitations. These fractionalized excitations are quasiparticles with properties distinct from conventional electrons, and their presence is inferred from experimental observations. The collective effect of charge order, broken symmetry, and fractionalized excitations creates a highly correlated electronic environment that deviates significantly from traditional Fermi liquid theory, and is believed to be crucial for understanding the mechanisms behind high-temperature superconductivity in these materials.

A Converging Picture: Implications and Future Directions

A compelling and unified understanding of the electronic structure within underdoped cuprates emerges from the synergistic application of several advanced experimental and theoretical techniques. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) directly maps the momentum-dependent electronic structure, while scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) provides real-space imaging of the charge density modulations indicative of Fermi surface reconstruction. Crucially, quantum oscillation measurements, despite the challenges posed by these materials, confirm the topology of the reconstructed Fermi surface, and sophisticated theoretical modeling provides a framework to interpret these findings. The convergence of results from these distinct approaches-ARPES, STM, and quantum oscillations, all supported by robust theoretical calculations-establishes a consistent picture of how the electronic structure is fundamentally altered in these complex materials, offering critical insight into their unusual properties and paving the way for potential breakthroughs in superconductivity research.

The subtle curvature of the Fermi surface – the boundary separating filled and empty electron states – holds crucial information about a material’s electronic properties, and recent research demonstrates a powerful link between this curvature and a phenomenon called Sondheimer oscillations. These oscillations, observed in electrical resistance measurements, are directly related to the Gaussian curvature of the Fermi surface; a larger curvature results in a higher Sondheimer frequency. By meticulously analyzing the frequency of these oscillations, scientists can effectively ‘map’ the shape and topology of the Fermi surface without directly visualizing it. This indirect approach is particularly valuable in complex materials where direct observation is challenging, offering a new avenue for understanding how electrons behave and interact, and ultimately, for tailoring materials with desired electronic characteristics.

The emergence of a Spin Density Wave (SDW) within the electronic structure of underdoped cuprates provides a compelling explanation for their often-unexpected behaviors. This SDW, arising from the reconstruction of the Fermi surface – the boundary defining the highest energy electrons – fundamentally alters the material’s electronic landscape. Rather than a uniform electron distribution, the SDW creates a periodic modulation of spin and charge density, influencing properties like resistivity and magnetic susceptibility. This reconstruction and the resulting SDW account for the observed deviations from conventional metallic behavior, including the pseudogap phase and the peculiar temperature dependence of various physical quantities. The consistent observation of this SDW across different experimental probes strongly suggests it is not merely an artifact, but a crucial ingredient in understanding the complex interplay of electronic correlations and superconductivity within these fascinating materials.

A unified understanding of cuprate materials is emerging, offering not just explanation of their unusual electronic behavior, but also a route towards manipulating these properties. Research indicates that precise control over the complex interplay of electronic states within these materials is achievable, potentially unlocking further advancements in superconductivity. Crucially, the amplitude of Sondheimer oscillations – a key indicator of electronic structure – exhibits predictable behavior dependent on material characteristics and external conditions; specifically, oscillation amplitude diminishes exponentially with increasing film thickness, represented by e^{-d/v̄zτ}, and scales inversely with the fourth power of the applied magnetic field B^{-4}. This sensitivity provides a valuable diagnostic tool and suggests that carefully tailored film deposition and magnetic field application could be leveraged to optimize superconducting performance and explore novel electronic phases.

The pursuit of understanding complex systems, as demonstrated in this exploration of Sondheimer oscillations within cuprate superconductors, echoes a fundamental principle of elegant design. Just as clarity emerges from well-structured code, so too does a clearer picture of the Fermi surface arise from meticulous measurement of these magneto-oscillations. This research subtly reveals information; it doesn’t overwhelm with complexity. As Friedrich Nietzsche observed, “There are no facts, only interpretations.” The careful mapping of the Fermi surface via Sondheimer oscillations isn’t simply about discovering pre-existing truths, but rather constructing a coherent interpretation of the underlying quantum reality, offering insight into the elusive pseudogap phase. Beauty scales, clutter does not, and this method provides a scaling path to understanding.

Beyond the Surface

The proposition that Sondheimer oscillations can serve as a temperature-independent lens for mapping the Fermi surface of underdoped cuprates feels, at first glance, almost too clean. Nature rarely offers such direct access. Yet, the underlying principle – that semiclassical transport can reveal quantum intricacies – is elegantly compelling. The immediate challenge lies not merely in detecting these oscillations – a feat already demanding considerable experimental finesse – but in rigorously disentangling the information they convey. The Fermi surface of these materials is not a static entity; its reconstruction within the pseudogap phase presents a moving target, and accurately resolving these dynamic shifts will require a delicate interplay between experiment and sophisticated theoretical modeling.

A good interface is invisible to the user, yet felt. Similarly, a good theoretical framework should yield predictions that are not merely consistent with the data, but illuminate the underlying physics with minimal adjustable parameters. Current models, while progressing, still rely on approximations that obscure the fundamental mechanisms driving the pseudogap. Future work must prioritize the development of more robust and predictive theoretical tools, capable of interpreting the nuances of the Sondheimer oscillations and revealing the true nature of the Fermi surface reconstruction.

Every change should be justified by beauty and clarity. The field now stands at a juncture. Simply confirming the existence of Fermi surface features is insufficient. The goal is not merely to map the surface, but to understand why it takes the form it does – to reveal the interplay of electron correlations, charge density waves, and other competing orders that sculpt the electronic landscape of these remarkable materials.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11252.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- Resident Evil Requiem cast: Full list of voice actors

- Did Churchill really commission wartime pornography to motivate troops? The facts behind the salacious rumour

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- PlayStation Plus Game Catalog and Classics Catalog lineup for July 2025 announced

- Best Shazam Comics (Updated: September 2025)

- Disney+: Everything Being Added in December 2025

2026-02-14 04:04