Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new framework dynamically adjusts sampling rates based on signal characteristics, potentially overcoming limitations of traditional data acquisition methods.

This work presents an algorithm-encoder co-design for adaptive non-uniform sampling, achieving accurate signal reconstruction while relaxing Nyquist-rate constraints through iterative reconstruction and energy-based convergence analysis.

Traditional sampling approaches often adhere to strict Nyquist rate constraints, limiting data acquisition efficiency for signals exhibiting varying complexity. This paper, ‘Adaptive Non-Uniform Sampling of Bandlimited Signals via Algorithm-Encoder Co-Design’, introduces a novel framework that dynamically adjusts sampling density based on localized signal characteristics, achieving substantial reductions in data volume without compromising reconstruction fidelity. By establishing an energy-based sufficient condition for convergence of iterative reconstruction algorithms, a variable-bias, variable-threshold time encoding machine is designed to enforce this criterion, even permitting sub-Nyquist sampling rates in slowly varying regions. Can this algorithm-encoder co-design paradigm unlock further advancements in efficient signal acquisition across diverse applications, from medical imaging to structural health monitoring?

The Illusion of Perfection: Why Traditional Sampling Fails

The foundational Shannon-Nyquist Sampling Theorem establishes that a signal can be perfectly reconstructed from its samples, provided the sampling rate exceeds twice the signal’s highest frequency component; however, this principle often necessitates a uniformly high sampling rate even when the signal’s frequency content isn’t constant. This approach proves remarkably inefficient because it acquires an equivalent level of detail across the entire signal duration, irrespective of whether high or low frequencies are actually present at a given time. Consequently, a considerable amount of redundant data is often collected, inflating storage requirements and computational load without contributing to improved signal representation. This limitation is particularly pronounced when dealing with non-stationary signals – those whose frequency characteristics change over time – where a fixed, high sampling rate represents a significant waste of resources, prompting exploration into more adaptive and efficient sampling strategies.

The act of digitizing a signal necessitates a trade-off between data volume and fidelity; acquiring too little data, known as undersampling, results in aliasing – a distortion where high-frequency components masquerade as lower ones, irrevocably corrupting the original information. Conversely, capturing excessive data through oversampling introduces significant redundancy, needlessly inflating storage requirements and computational load without proportionally improving signal accuracy. This impacts practical applications significantly, as the balance between these two extremes dictates the efficiency of data acquisition systems and the resources needed for subsequent analysis and processing. Effectively, both strategies represent suboptimal approaches; aliasing destroys information, while oversampling wastes it, highlighting the need for more intelligent and adaptive sampling techniques.

The challenges posed by traditional sampling methods become strikingly apparent when applied to intricate signals common in diagnostic and non-destructive testing. Accurate reconstruction of Electrocardiogram (ECG) signals, vital for cardiac monitoring, and Ultrasonic Guided-Wave signals, used in structural health assessments, demands a substantial number of samples – typically 2000 for ECG and 1966 for ultrasonic guided waves – when employing conventional, uniformly-spaced sampling. This high sampling rate translates directly to increased data storage requirements and computational burden. The necessity for such extensive datasets highlights a fundamental inefficiency, particularly as these signals often contain periods of relative inactivity or predictable behavior where a reduced sampling rate would suffice without compromising accuracy, prompting exploration into more adaptive and efficient sampling strategies.

Beyond Fixed Rates: A Dynamic Approach to Signal Acquisition

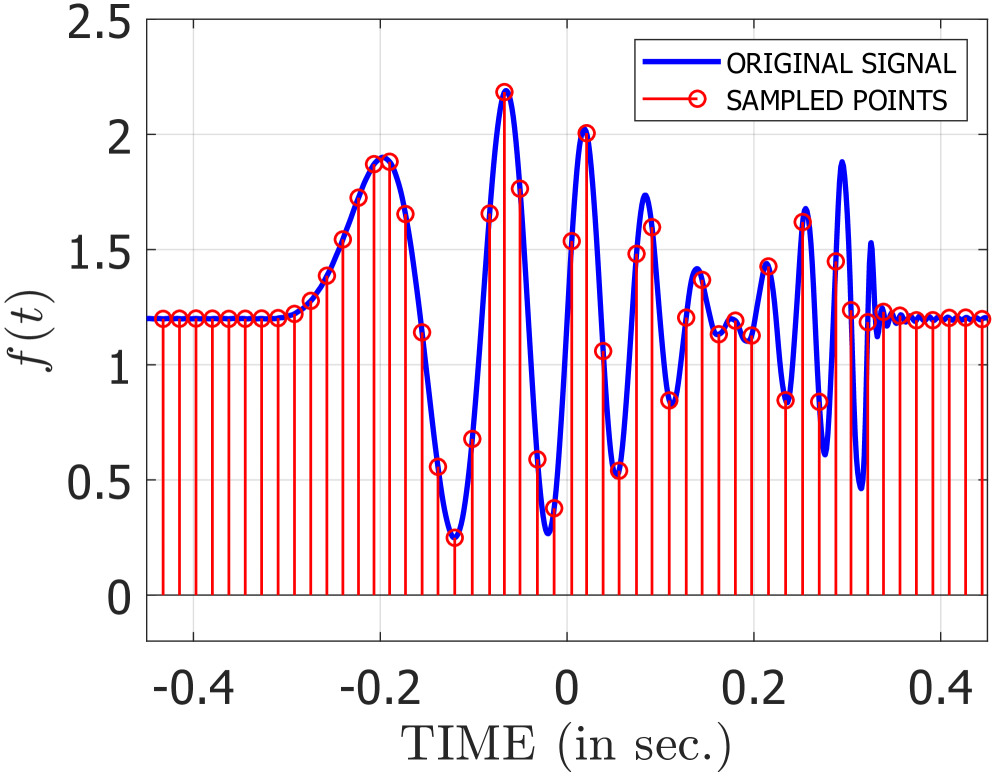

Adaptive Non-Uniform Sampling (NUS) departs from traditional fixed-rate sampling by modulating the sampling frequency based on real-time signal analysis. This dynamic adjustment prioritizes data acquisition where signal variations are most significant, effectively allocating more samples to complex or rapidly changing portions of the signal. By identifying and focusing on these critical regions, NUS minimizes the need for consistently high sampling rates across the entire signal duration, leading to efficient data capture and reduced redundancy. The process relies on algorithms that continuously assess local signal characteristics – such as magnitude, frequency content, or rate of change – to determine the optimal sampling rate at each point in time.

Most real-world signals exhibit temporal variations in energy distribution; that is, certain segments contain significantly more relevant information than others. Adaptive Non-Uniform Sampling (NUS) capitalizes on this non-uniformity by allocating a greater density of samples to signal portions characterized by high energy or rapid change, and conversely, reducing the sampling rate in regions of relative quiescence. This targeted approach contrasts with traditional uniform sampling, which applies a constant sampling rate across the entire signal duration, irrespective of local characteristics. The result is an efficient allocation of resources, focusing precision where it is most impactful and reducing redundancy elsewhere.

Adaptive Non-Uniform Sampling (NUS) provides an efficient alternative to traditional uniform sampling by reducing the total number of samples required for accurate signal reconstruction. Experimental results demonstrate that NUS can achieve up to a ~6% reduction in the number of samples needed, without compromising signal fidelity. This reduction translates directly into lower data storage requirements and decreased computational load for subsequent signal processing tasks. The method accomplishes this by strategically allocating samples based on signal characteristics, effectively capturing critical information with fewer data points than would be necessary with a fixed sampling rate.

Reconstructing the Truth: Ensuring Accuracy in Imperfect Data

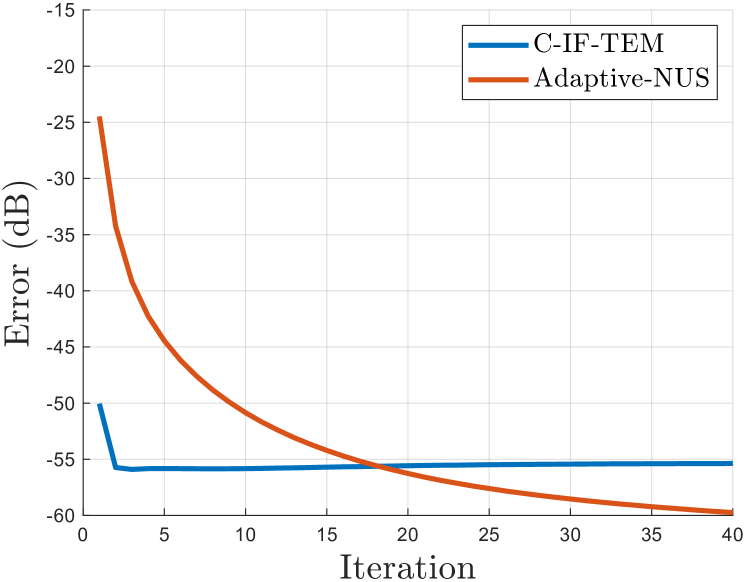

Iterative reconstruction algorithms are fundamental to signal recovery when data is acquired through non-uniform sampling. Unlike traditional methods reliant on consistent intervals, these algorithms operate by initially forming an estimated signal based on the irregularly sampled data. Subsequent iterations then refine this estimate by minimizing the difference between the acquired samples and the reconstructed signal, effectively projecting the estimate closer to the true signal with each cycle. This process continues until a predetermined convergence criterion is met, ensuring an accurate representation of the original signal despite the non-uniform sampling pattern. The iterative nature allows for leveraging all available data points, even those acquired at varying time intervals, to improve the quality of the reconstruction.

Convergence analysis for iterative reconstruction algorithms is a critical step in validating their performance and ensuring a stable, accurate reconstructed signal. This process mathematically demonstrates that, with each iteration, the algorithm approaches a unique, fixed-point solution, rather than oscillating or diverging. Establishing convergence provides a quantifiable guarantee of reliability; without it, the reconstructed signal’s fidelity cannot be assured, regardless of empirical results. Specifically, this analysis involves bounding the error between successive iterations and proving that this error diminishes with each step, ultimately reaching a negligible value. Demonstrations of convergence, such as those achieved through the Local Energy-Based Condition, are essential for deploying these algorithms in practical applications where signal integrity is paramount.

The Local Energy-Based Condition establishes a sufficient criterion for the convergence of iterative reconstruction algorithms applied to signals possessing localized energy. This condition mathematically guarantees the algorithm will reach a stable solution, validating its reliability for signal recovery. Empirical results demonstrate the efficacy of this framework; reconstruction of ultrasonic guided waves using only 1856 samples achieved a Normalized Mean Squared Error (NMSE) of -42.68 dB, while reconstruction of ECG signals using 1837 samples resulted in an NMSE of -32.45 dB. These values indicate a high degree of accuracy in signal recovery under the specified conditions and sampling rates.

Beyond Amplitude: Encoding Signals as Events in Time

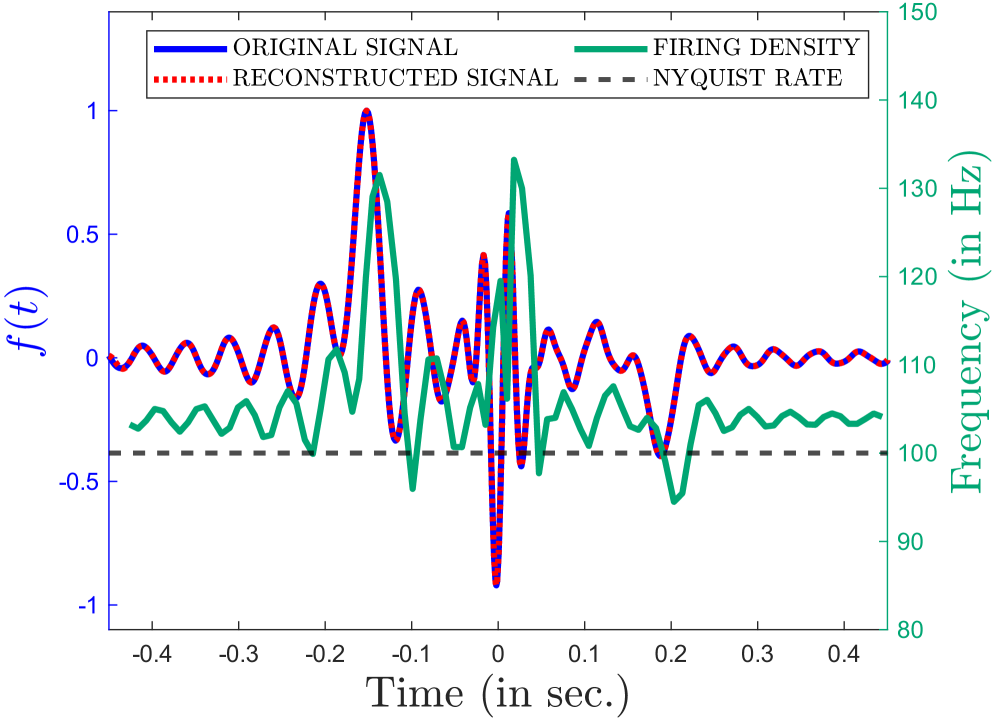

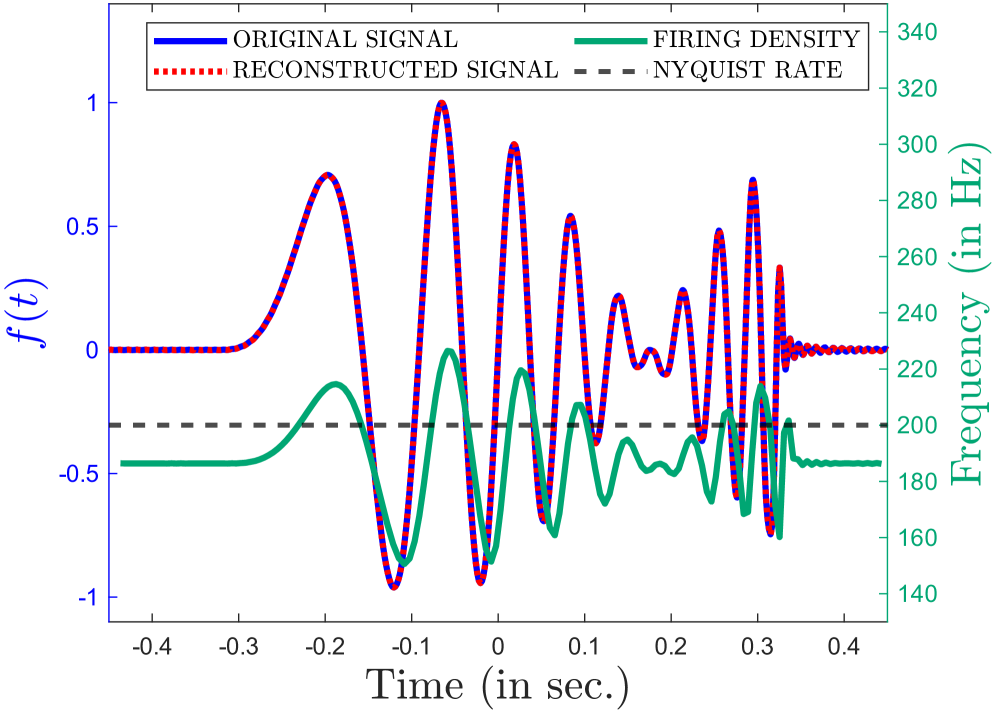

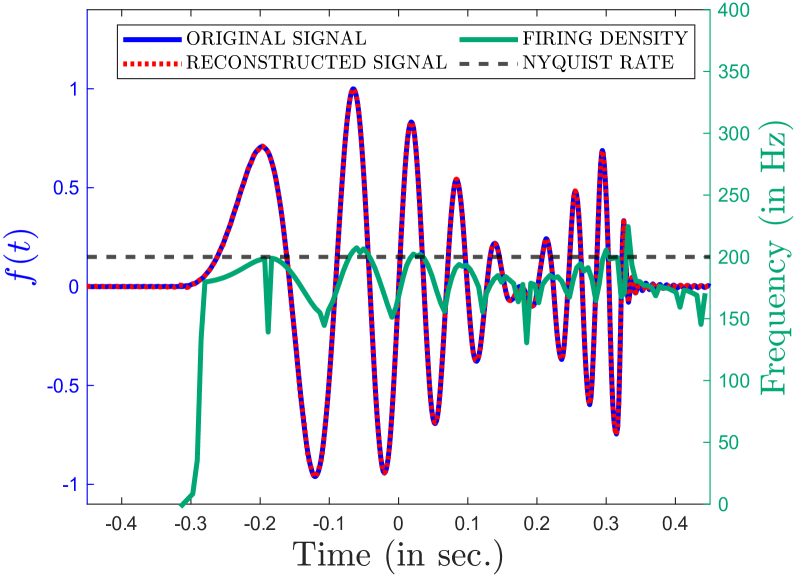

Conventional signal representation relies on capturing the amplitude of a wave at discrete points in time, demanding high sampling rates to avoid losing information. Time Encoding Machines (TEMs) challenge this paradigm by focusing instead on the timing of events; a signal isn’t defined by how strong it is, but by when something happens. This approach fundamentally shifts the focus from continuous amplitude values to precise temporal markers, offering a potentially more efficient way to encode information. By representing signals through these carefully orchestrated timings, TEMs can achieve accurate reconstruction with far fewer samples than traditional methods, particularly for signals possessing specific characteristics like increasing or decreasing frequency. The resulting encoding isn’t a depiction of signal strength, but a carefully constructed sequence of events in time, unlocking new possibilities in data compression and signal processing.

Integrate-and-Fire Time Encoding Machines (IF-TEMs) refine the concept of temporal encoding by mimicking the behavior of biological neurons. Instead of directly representing a signal’s strength with amplitude, IF-TEMs accumulate input over time – integrating the signal until a predefined threshold is reached. Upon reaching this threshold, the system “fires,” emitting a signal that represents the event’s timing. This process creates a sparse representation, meaning only a limited number of events are recorded, dramatically reducing the required data volume for signal reconstruction. The efficiency stems from encoding information in the intervals between these firing events, rather than continuous amplitude values, offering a potentially powerful method for compressing and processing signals, especially those with complex temporal structures.

A key advantage of Time Encoding Machines lies in their capacity to dramatically reduce the data required for accurate signal representation. Traditional methods rely on high sampling rates to capture signal amplitude, but TEMs leverage the timing of events, achieving comparable reconstruction quality with far fewer samples. This is particularly evident with complex signals like Chirp Signals – which exhibit changing frequencies – and Sum-of-Sincs (SoS) Signals, often used in signal processing as a foundational test case. By focusing on when a signal event occurs, rather than how strong it is, these techniques effectively compress information, offering substantial benefits for data storage, transmission, and real-time processing applications where bandwidth or memory are limited. The sparse nature of the encoding, achieved through integrate-and-fire mechanisms, further contributes to this efficiency, potentially revolutionizing how signals are handled in diverse fields.

The pursuit of efficient data acquisition, as detailed in this work, isn’t merely a technical exercise; it’s a reflection of humanity’s inherent drive to extract maximum information with minimal effort. The algorithm-encoder co-design, dynamically adjusting sampling rates based on local signal characteristics, suggests an understanding that absolute precision is often a costly illusion. As Niels Bohr once observed, “The opposite of a trivial truth is also trivial.” This resonates deeply; the traditional Nyquist-rate constraint, while seemingly fundamental, proves adaptable when viewed through the lens of energy-based conditions and iterative reconstruction. The framework doesn’t dispute the underlying physics, but rather reframes the approach, acknowledging that optimal solutions often lie not in rigid adherence to rules, but in intelligent deviations.

What Lies Ahead?

This work, predictably, opens more questions than it closes. The promise of sampling below the Nyquist rate is eternally seductive – a perpetual motion machine for data acquisition. Yet, the energy-based condition, while mathematically neat, feels like shifting the cost, not eliminating it. One suspects the true limitation isn’t the algorithm itself, but the inherent noise floor of any physical measurement. Humans crave efficiency, but rarely acknowledge the price of squeezing more information from less.

The co-design aspect – the dance between encoder and decoder – hints at a deeper truth. Signal processing isn’t about finding the ‘right’ representation, it’s about crafting a shared delusion between sender and receiver. The more complex the encoding, the more vulnerable the system becomes to subtle distortions, to the inevitable drift from ideal conditions. Future work will undoubtedly focus on robustness – on making these adaptive systems resilient to the messy reality of implementation.

One can foresee a proliferation of these ‘time encoding machines,’ each tailored to a specific signal type, a particular environment. The real competition won’t be about achieving the absolute lowest sampling rate, but about minimizing the regret when the underlying assumptions inevitably fail. Bubbles are born from shared excitement and die from lonely realization; this field, like all others, will eventually confront its own limits.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15790.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- When Is Hoppers’ Digital & Streaming Release Date?

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Samson: A Tyndalston Story Studio Wants Players to Learn Street Names, Manage Hour-to-Hour Pressure

- 10 Best Anime to Watch if You Miss Dragon Ball Super

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- PlayStation Plus Game Catalog and Classics Catalog lineup for July 2025 announced

- Did Churchill really commission wartime pornography to motivate troops? The facts behind the salacious rumour

- Wicked Recap: 5 Biggest Things To Remember Before Watching Wicked: For Good

2026-01-26 00:20