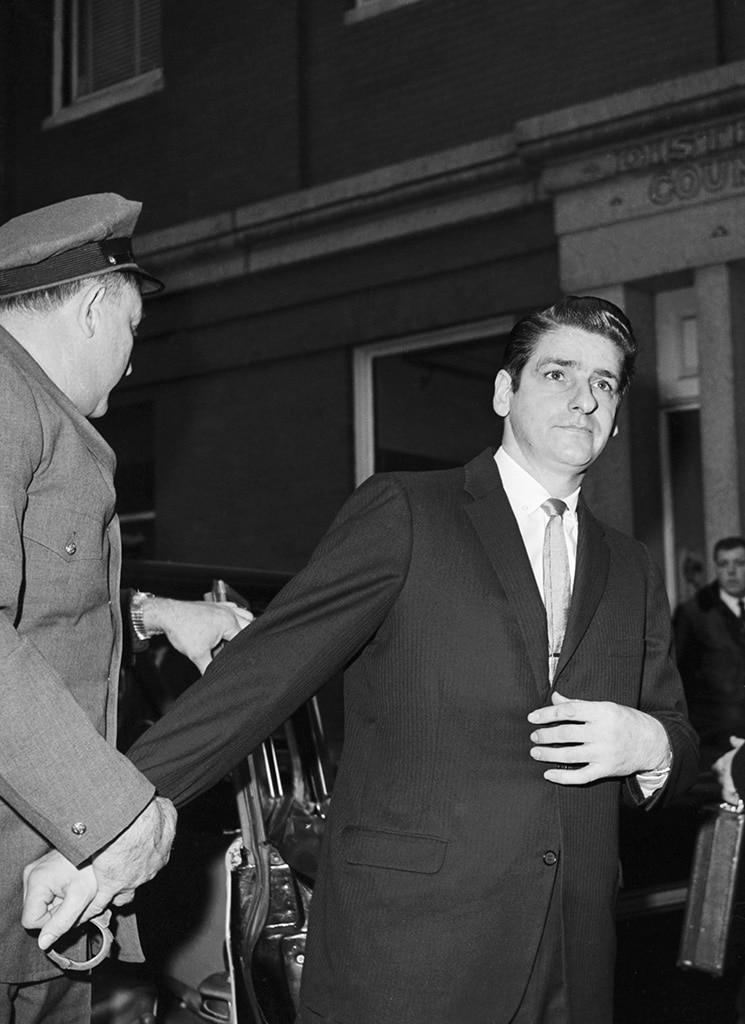

When Albert DeSalvo was arrested by Cambridge, Mass., police in November 1964, it wasn’t for murder.

Rather, the 33-year-old handyman was wanted for robbery and sexual assault.

Following a determination that he was not mentally competent to face trial for rape, he was committed to a psychiatric hospital. While there, he confessed to attorney F. Lee Bailey that he had murdered 12 women, including 11 linked to the crimes known as the “Boston Strangler.” This nickname was created by reporters Loretta McLaughlin and Jean Cole of the Record-American newspaper.

Although DeSalvo received a life sentence for ten rapes, he later took back his confession. He was never accused of the murders, and he died in prison in 1973 after being stabbed.

As a true crime enthusiast, I’m completely hooked by the new Oxygen documentary, The Boston Strangler: Unheard Confession, which starts October 26th. It really makes you question everything you thought you knew – the film explores the possibility that Albert DeSalvo might not have been the actual serial killer, which is fascinating considering people didn’t even use that term back then.

Following the case, several dramatizations appeared, beginning with the 1968 film The Boston Strangler, which featured Tony Curtis as the seemingly guilty DeSalvo and Henry Fonda as prosecutor John Bottomly.

According to an expert featured in the Oxygen documentary, there was no evidence linking him to the murders. The documentary includes previously unheard portions of over 50 hours of recordings detailing DeSalvo’s confession, tapes that had been missing for decades until Casey Sherman located them.

Sherman’s aunt, Mary Sullivan, was tragically murdered in her Boston apartment on January 4, 1964. She is remembered as the last victim of the Boston Strangler, a notorious criminal from that era.

In the documentary, Sherman, author of A Rose for Mary and Search for the Strangler, explains that his mother always doubted Albert DeSalvo’s confession, and now he understands why the Boston Police Department kept the tapes secret.

Despite numerous alleged murders attributed to the Boston Strangler, forensic evidence directly connects Albert DeSalvo only to the Sullivan case.

Here’s a breakdown of Albert DeSalvo and the Boston Strangler case. While officially closed by authorities, the case continues to spark debate and unanswered questions.

The crime scene details presented here are based on Gerold Frank’s book, The Boston Strangler. Frank’s research, which won an Edgar Award, drew from police and court records, medical reports, interview transcripts, and his own investigations.

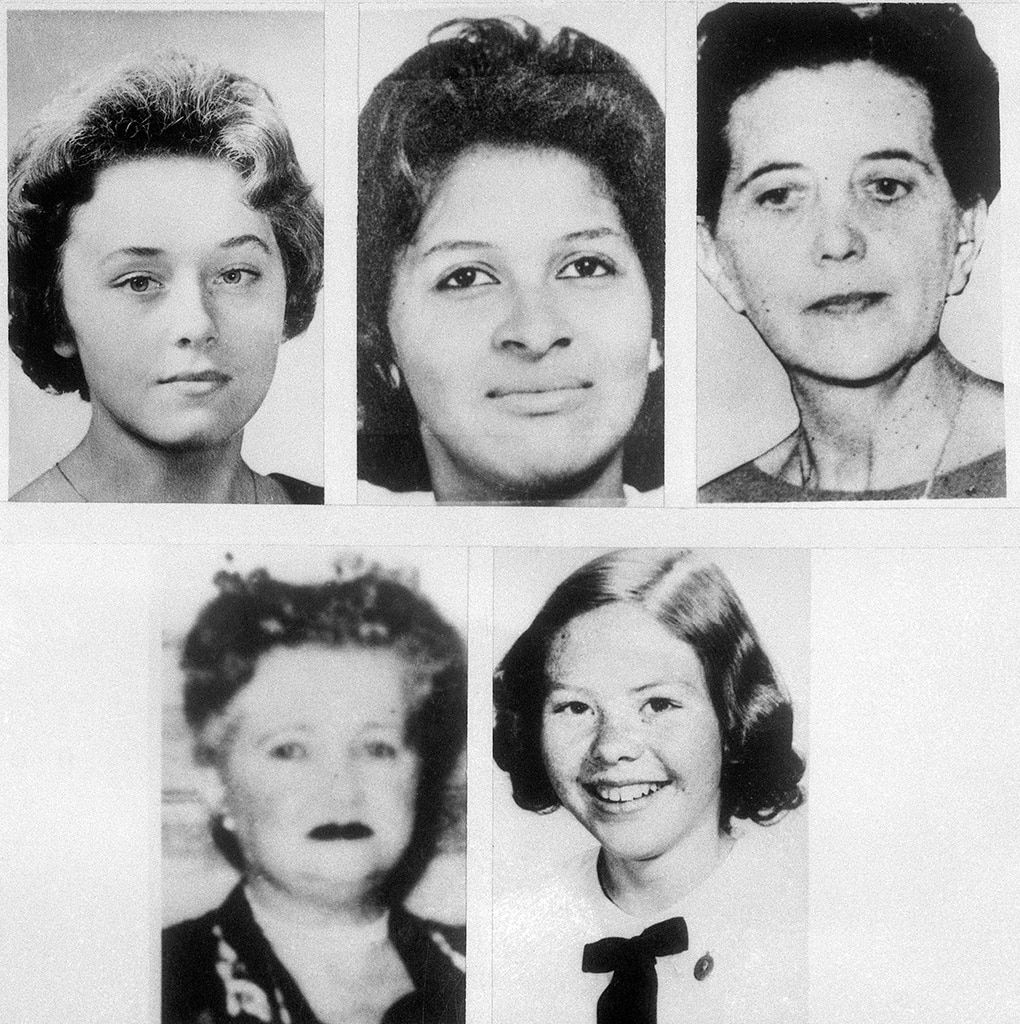

The first victim linked to the Boston Strangler was Anna Slesers, a 55-year-old seamstress who lived alone in Boston’s Back Bay. On June 14, 1962, at 7:45 p.m., her 25-year-old son discovered her while arriving to take her to church. He found her lying in the hallway near the bathroom and initially thought she had committed suicide by hanging herself with her bathrobe cord.

When Officer James Mellon of the Boston Police arrived, he immediately suspected foul play. The partially filled bathtub, warm muffins still in the kitchen, and the way Slesers lay—her robe open and body exposed—told him this wasn’t an accident, but a murder.

On June 30th, Nina Nichols, 68, didn’t arrive at her sister’s for dinner, prompting her brother-in-law to ask the building superintendent to check on her. The superintendent found Nichols in her fourth-floor apartment, lying on the bedroom floor. She had been strangled with her own stockings, and her robe was pulled up, leaving her partially exposed.

After not seeing their neighbor, Helen Blake, for the entire weekend, two residents of her Lynn, Massachusetts building asked the building superintendent for a key. They checked on her around 5 p.m. on July 2nd and, finding her unresponsive and lying face down on the bed with her pajamas partially up, immediately called the police. Blake was 65 years old.

Blake was strangled with a stocking, and her bra straps were tied under her chin in a loose bow—a method similar to the way the robe cord of Slesers and the stockings of Nichols were tied. Investigators confirmed Blake was also killed on June 30th.

On August 22nd, 75-year-old Ida Irga was discovered on the floor of her Boston apartment. Police determined she had been strangled, and a pillowcase was found tied around her neck.

As a lifestyle expert, I’m sharing details of a truly tragic case. On August 30th, police discovered 67-year-old Jane Sullivan murdered in her Dorchester apartment. It was a heartbreaking scene – she was found strangled with her own stockings, posed kneeling in her bathtub, and had been deceased for several days. The water in the tub covered her face and forearms, adding to the grim discovery.

Investigators discovered the items used to tie around the women’s necks were all secured with a simple knot commonly called a granny knot.

When news broke that both Nichols and Blake had been murdered on the same day, police created a round-the-clock emergency line – as 911 didn’t exist yet – and advised women to lock their doors, avoid letting strangers in, and report anyone who seemed suspicious.

According to Frank’s book, Police Commissioner Edmund McNamara was concerned about causing public panic. While he dedicated all available officers to the murder investigation and sent many detectives to an FBI seminar on sex crimes, he deliberately limited the information shared with the public.

However, the hotline continued to receive numerous reports of concerning behavior. It became clear that many men were harassing women, even if they weren’t committing violent crimes.

The discovery of Irga as the fourth victim caused public fear to escalate rapidly. People were so scared that women wouldn’t even allow police officers into their homes, forcing detectives to question Irga’s frightened neighbors from outside their locked doors.

Following the deaths of Irga and Sullivan, the Boston Herald published an editorial attempting to reassure the public, stating the likelihood of becoming a victim was “almost nil.” Meanwhile, the Boston Advertiser took a different approach, publishing an open letter on its front page directly to the Strangler, encouraging him to reach out to the newspaper for assistance.

After Irga’s murder in August 1962, medical reporter Loretta McLaughlin became increasingly focused on the case. She proposed a series of articles about the killings to her editor at the Boston Record American, but he didn’t believe readers would be interested and declined her idea.

In a later article for the Boston Globe, McLaughlin recalled an editor dismissing the significance of the series about the four murdered women, pointing out they were unremarkable people. McLaughlin realized this was precisely what made the case so compelling. Why would someone kill four women no one knew? He felt their anonymity—a shared fate with everyone—was what drew him to the story.

I remember being absolutely horrified when I first learned about Sophie Clark. She was just 20, a nursing student sharing an apartment in Back Bay, and she was found murdered on December 5th, 1962 – sexually assaulted and strangled with her own stockings. What really stuck with me, and what Frank detailed in his book The Boston Strangler, was that this was the first time investigators found semen near one of the victims. It was a chilling detail that made the case feel even more brutal and personal.

On December 31st, 23-year-old Patricia Bissette was discovered in the same area, according to Frank. She was found in bed, covered with blankets, which hid the stockings and white silk blouse tied around her neck.

Okay, so after Bissette was murdered, McLaughlin and Jean Cole – honestly, they were amazing on this case – they took over. And unlike so many others, even the top brass, they quickly became convinced it was all the work of just one person. I mean, they just got it, you know? They saw the pattern where everyone else was stuck on multiple suspects. It was brilliant, honestly!

On May 8, 1963, 23-year-old Beverly Samans, a Boston University graduate student, was found dead in her Cambridge apartment by her fiancé. As detailed in Frank’s book, The Boston Strangler, she appeared to be lying on her couch, with stockings around her neck and wrists tied with a shimmering scarf. However, the initial appearance was misleading – Samans had actually been stabbed twenty-two times, and the stockings were merely placed there to create a false impression.

On September 8, 1963, 58-year-old Evelyn Corbin was discovered strangled in her Salem apartment. She had stockings used as a ligature, and her mouth was stuffed with underwear. A pair of stockings was tied around her left ankle in a bow.

On November 23rd, just one day after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, 23-year-old Joann Graff was found raped and strangled in her Lawrence, Massachusetts apartment. She had been tied with stockings, which were loosely knotted around her neck, and also had bite marks on her left breast.

On January 4th, 1964, two friends came home to their apartment on Beacon Hill and discovered their new roommate, 19-year-old Mary Sullivan, murdered in bed. Frank described the scene as even more terrifying than the ten previous strangulations. A stocking around her neck and a large pink silk bow were telltale signs of the killer’s method.

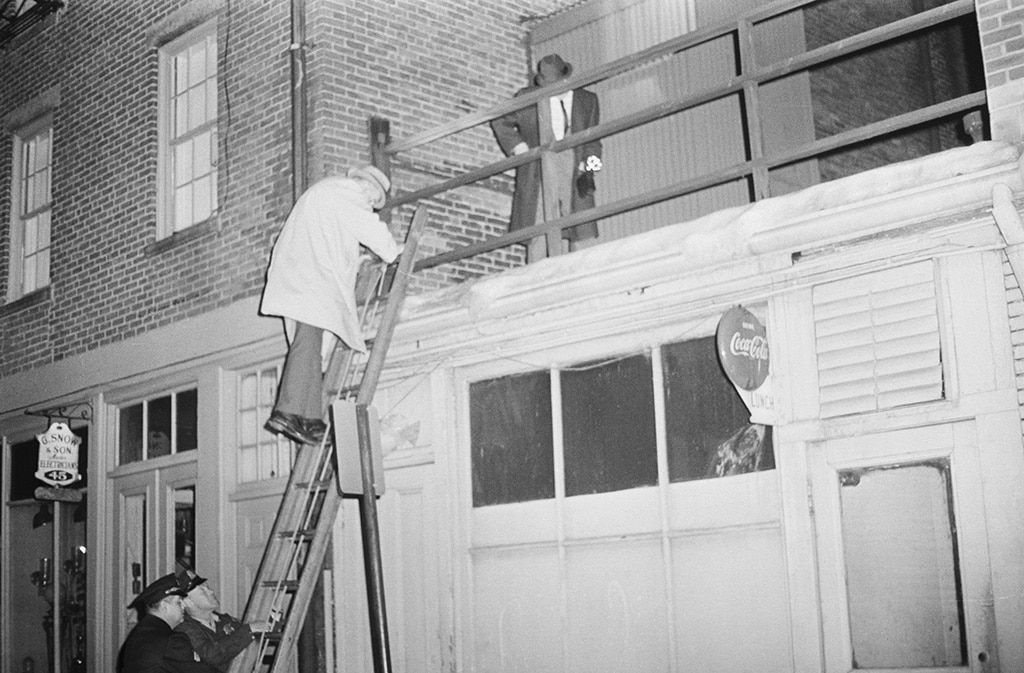

On Oct. 27, 1964, a 20-year-old newlywed reported to police that she’d been tied up and sexually assaulted in her Cambridge apartment. She said her attacker held a knife to her throat and told her not to look at him, but she did—and the description she gave resembled a criminal dubbed the “Measuring Man.”

Albert DeSalvo, a husband and father of two, had previously served two years in prison for attempted burglary and assault. He often pretended to be a modeling scout to gain access to women’s apartments, claiming he needed to take their measurements. Known as the “Measuring Man,” DeSalvo was released from prison on April 9, 1962, just two months before a series of stranglings began.

A 33-year-old man was arrested on November 3, 1964, and denied involvement in an assault that occurred on October 27th. He was released on $8,000 bail. After his photo was made public, police in Connecticut learned that four women in separate towns had reported being attacked on May 6, 1964, and they believed he matched the description of their assailant.

DeSalvo was arrested once more on November 5th. He refused to speak to police until his wife arrived at the station. With officers present, he then told his wife he had “done some very bad things with women,” but insisted he had never committed murder.

According to reports, his wife, Irmgard DeSalvo, urged him to admit everything. He then confessed to detectives that he’d committed over 400 burglaries and also admitted to a couple of rapes that hadn’t been discovered. However, he maintained his innocence regarding the strangling murders.

Albert DeSalvo, who had been diagnosed with sociopathic tendencies, schizoid features, and depression, was moved from jail to Bridgewater State Hospital. He was found unfit to stand trial for the rapes he was accused of and was committed to the psychiatric facility on February 4, 1965. While there, he began revealing details about the crimes that only the Boston Strangler would likely know to a fellow inmate named George Nassar.

Nassar contacted his attorney, F. Lee Bailey, a lawyer well-known for previously defending Albert DeSalvo and later becoming part of O.J. Simpson’s famous defense team.

In a recorded conversation with Bailey, DeSalvo confessed to murdering all eleven previously mentioned women, and also admitted to killing 69-year-old Mary Brown in Lawrence on March 9, 1963. He also stated that he had intended to kill another woman in 1962, 85-year-old Mary Mullen, but she died of a heart attack before he could.

Bailey always insisted that DeSalvo was the Boston Strangler, and he used his client’s confession to a murder to support his claim that the client was not mentally capable of committing rape. He held this belief for the rest of his life.

Despite investigators showing pictures of DeSalvo to people in the buildings and surrounding areas, no one who remembered seeing a suspicious man around the time of the murders could identify him.

According to Frank, investigators—including Assistant Attorney General John Bottomly—didn’t believe the prisoner was being truthful. They also considered the possibility that Larry Nassar, who would later be convicted of a different murder, was actually the real killer and was attempting to frame DeSalvo for the other crimes.

During the summer of 1965, Bottomly interviewed DeSalvo repeatedly, trying to determine if he was indeed the Boston Strangler.

DeSalvo provided detailed accounts of the crimes. Detectives Bottomly and the lead investigators began to suspect he was the actual killer, particularly when he revealed a correct detail that hadn’t been reported accurately in the news – a mistake had been made in the original police report.

According to Frank, when DeSalvo was released from jail, he was labeled as someone who committed burglary, not sexual assault. This meant investigators didn’t consider him a suspect when they were reviewing records and looking for potential matches to the crimes.

Although some of the things DeSalvo confessed during more than 50 hours of interviews – resulting in 2,000 pages of transcripts – couldn’t be proven, he was largely accurate. Investigators confirmed most of the details he shared.

On June 30, 1966, the court determined Albert DeSalvo was mentally capable of facing trial for the series of rapes known as the “Green Man” attacks, a nickname given because victims remembered the attacker wearing green work pants.

DeSalvo entered a plea of not guilty, and his lawyer, Bailey, maintained that the jury had no option but to declare him legally insane, ensuring he would receive the necessary mental health care. However, on January 18, 1967, DeSalvo was found guilty on ten counts of rape and armed robbery, resulting in a life sentence.

After the verdict, Bailey spoke to reporters, stating, ‘Massachusetts has condemned another innocent woman as a witch.’ He quickly added that the jury wasn’t to blame, but rather the unjust laws themselves were at fault.

On February 24th, DeSalvo and two other prisoners broke out of Bridgewater. He was recaptured the following day at a clothing store in Lynn and, as a result, was moved to a higher-security prison, now known as the Massachusetts Correctional Institution—Cedar Junction.

DeSalvo later took back his confession. He was killed by another prisoner in the prison hospital on November 25, 1973, and was never officially charged with any of the Boston Strangler murders.

In July 2013, officials stated they had found DNA from family members that connected DeSalvo to the 1964 murder of Mary Sullivan. To verify this, they examined DeSalvo’s remains and determined there was only a one in 220 billion chance the DNA belonged to another person. This was the first forensic evidence supporting DeSalvo’s confession.

Since the confession was first made, people have questioned its validity and it’s been a source of debate,” said Suffolk County District Attorney Daniel Conley at a press conference announcing the findings. He admitted there’s no widespread agreement that DeSalvo was the Boston Strangler, and pointed out that the evidence only connects him definitively to one victim – a case complicated by the victim’s nephew, who had previously suggested multiple people were responsible.

Former State Attorney General Martha Coakley expressed hope that this would provide closure for Mary Sullivan’s family. She stated that the evidence clearly showed Albert DeSalvo was responsible for Mary Sullivan’s murder, and likely responsible for the deaths of the other women he admitted to killing.

You can watch “The Boston Strangler: Unheard Confession” on Oxygen True Crime starting Sunday, October 26th, at 6 p.m. Eastern and Pacific time.

Read More

- How to Get the Bloodfeather Set in Enshrouded

- Every Targaryen Death in Game of Thrones, House of the Dragon & AKOTSK, Ranked

- The Pitt Season 2, Episode 7 Recap: Abbot’s Return To PTMC Shakes Things Up

- 4 TV Shows To Watch While You Wait for Wednesday Season 3

- Where Winds Meet: How To Defeat Shadow Puppeteer (Boss Guide)

- Best Thanos Comics (September 2025)

- One of the Best EA Games Ever Is Now Less Than $2 for a Limited Time

- Felicia Day reveals The Guild movie update, as musical version lands in London

- Goat 2 Release Date Estimate, News & Updates

- 10 Movies That Were Secretly Sequels

2025-10-25 15:19